Back in June, the American Medical Association delegates voted against the conclusions by their internal Council on Science and Public Health. The council concluded obesity should NOT be defined as a disease because the Body Mass Index (MBI) used to measure obesity has issues “simplistic and flawed”.

Arguments for classifying obesity as a disease included the following:

more attention to obesity by the medical community,

reduction of stigma against those who are obese,

fits “some” of the criteria that makes a disease,

obesity can lead to heart disease and diabetes.

—AMA recognizes obesity as disease

When I originally read about this over the summer, I wasn’t persuaded by the reasons for defining obesity as a disease, and it seemed like the medicalization of obesity might actually persuade people that there was not much they could do to help treat their condition.

And then I came across this article yesterday: “What harm is there in labeling obesity a disease”

Turns out that some researchers wanted to document how the naming of obesity as a disease “has influenced health and diet messaging.” The results show that messages related to obesity can affect a person’s attitude towards their health and actually lead to less attempts at getting healthy. (Read the article for more specifics.)

All of this reminds of the time I requested my medical records back in 2012 after I was diagnosed with prediabetes. I wanted to understand things from the medical/scientific side of things. In the first line, I was described as a morbidly obese women. I’m thinking that a person should never really be described as morbid. I mean, it means unhealthy (ok, fine, that was true), unwholesome, gruesome.

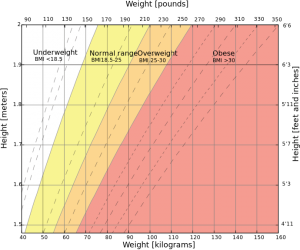

But here’s the real issue for me: the measure of obesity is the body mass index (BMI). BMI is calculated by the ratio of height and weight, and a BMI of 30 or above is considered obese. That’s how one is diagnosed as having obesity. Yes, in some cases, measurements are made, and there’s research to show that the risk for a whole host of conditions and diseases is caused by obesity. However, none of this actually helps the person who is diagnosed. And treatments for obesity are losing weight, exercising, and surgery. I promise you that lots of people who are obese are experts as losing and gaining weight. What it also means is that a person can be healthy, fit, and obese.

And even more troubling is that BMI is now the gold standard for qualifying for weight loss surgery and in measuring the success rates. BMI was never meant to diagnose anything is only part of the issue here. It’s now being used to diagnose and qualify people (mostly women) for risky surgeries that change what they can and can’t do with their body. So what if we questioned the use of BMI in this way? What if we questioned why losing weight or BMI is the gold standard for health? Is it really about health or is it about reaching some ideal weight?

I’m been thinking lots about these kinds of questions lately as I made a decision NOT to have weight loss surgery because for me this last journey has never been about weight loss, it’s been about being full of healthy behaviors and habits. The weight loss has actually been the lagnaippe in my journey.

And to think, according to all of these charts and graphs and the medical establishment, I am still quite obese. Yesterday, I walked six miles because we had a snow day and I had the time to do it. I certainly feel pretty darn good about that. This is just the beginning of my writing on this issue. I welcome comments and feedback.

Thanks for these thoughts Michelle! I agree that BMI is an inadequate measure of health and has been for over a decade when I first recall hearing about charging airline passengers for extra seats based on their BMIs. At the time, I lived with a varsity athlete who was five feet of nothing but muscle, which would have made her obese (muscle density as opposed to fat density is a matter you might consider), thereby forcefully begging the question of why BMI would be a (n overly reductive) measure of health (can we measure that quantitatively or is in necessarily qualitative?). I am also always reminded though of Cynthia Whitehead-Laboo’s presentations on healthy activities and “ideals” perpetuated by the media, which bring the fore the importance of “act” over a number or other “talk”, but also because she reminds me that those ideals are racialized and vary across cultures. Addressing these issues together as intersectional is increasingly important as the media provides us one and not the other, disambiguating their intrinsic relationship. I look forward to your future thoughts and future conversations on these issues!

Makes me want to read Healthy At Every Size and throw away my scale.